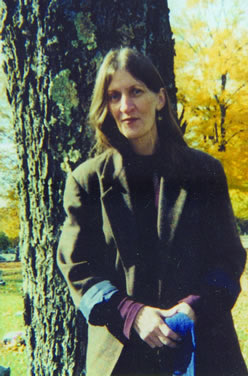

Ingrid Hill

|

Ingrid Hill has published stories in Black Warrior Review, Image, Indiana Review, the Michigan Quarterly Review, Shenandoah, the Southern Review, Story, and New Stories from the South. Her first short-story collection was Dixie Church Interstate Blues. She has had two NEA Fellowships in fiction. Her first novel, Ursula, Under, won the 2004 Great Lakes Book Award for fiction, was named a Washington Post Best Book of the Year, and was longlisted internationally for the Orange Prize. She has twelve children, including two sets of twins. She lives in Iowa City, where she is working on her next novel, Widows and Orphans. |

|

photo credit: Maria Gabriel Hill |

The Devil's Trampoline |

|

|

If, as Augustine of Hippo said, miracles are not contrary to nature but only to what we know of nature, magical realist fiction, abounding in miracle, may be framed as a peephole into the deepest, most vivid, redeemed, transcendent aspects of nature. If tragedy is incomplete comedy—a dire trajectory, descending but never rising again—magical realism is comedy bounding off tragedy's trampoline into another dimension. To get there, however, you have to be put through horror, a variant perhaps of the devil's sausage machine, something nobody healthy seeks out. Folks who haven't experienced the transmutation of evil to wondrousness think it's impossible. It's a version of the fridge magnet, "If life gives you lemons, make lemonade," taken to the nth degree. My sweet grandmother used to murmur consolingly, when I crabbed about the misery of sitting with hot rollers burning my scalp, "Honey, you have to suffer to be beautiful." Not till I was grown did I realize the deeper meaning: not till you have been cast into tribulation's depths, suffered in your core, can beauty shine out of your eyes or your art. In 1987, I was dropped into a situation that smashed the bounds of what I believed possible: my ex-husband abandoned me with 11 children. I know: simply having eleven children is beyond most folks' ken, but I grew up in New Orleans' Catholic culture. There it hadn't been weird. Kids were lovely, a blessing; divorce, nonexistent. Why he left? He'd said—in so many words—that he envied my writing; I didn't pick up the clue. But, hey, now I was free to write. I began living each day in miracle territory. Expecting astonishment, trusting in providence, living in hope. Won a canvas bag in a Popsicle sweepstakes. Won a graduate fellowship to Iowa. Daily one of my kids found a dollar in a pocket in clean laundry—or blowing down the street, no lie—just as the children of Israel went out each morning and found fresh manna for breakfast. My kids called the daily dollar-find a sign, decreed we'd spend it on a video. Not by bread alone, y'all! I didn't argue. I meandered through the living room, kids splatted on the rug watching a dollar videotape of Blues Brothers. Cab Calloway in white tie and tails sings and dances "Minnie the Moocher." Trying to capture the surrealness of that time, I lifted a phrase, "A Dream of the King of Sweden," from that song to title a story that was a more believable version of my own stranger-than-fiction experience. Minnie, abandoned, feels desperate, fantasizes that, wow, the King of Sweden might come along and rescue her. It's a joke; then again not. Thus, "trouble" in the so-called real world led me to start writing stories with elements of magical realism. High one day on invisible clouds of book dust in the UI library stacks, I found a book-length Gabriel García Márquez interview, "The Fragrance of Guava." It hooked me. Asked how he developed his magical realist style, García Márquez demurred: it wasn't a style at all, just his way of articulating how things looked to him as a child. His child-mind took over. Then, from another angle: it was the meeting of an oppressive class system—United Fruit was running Colombia—with the banks of flickering candles in red glass and swinging censers of incense that comprised Colombia's superstitious version of Catholicism. Jeez: in New Orleans in my childhood, my father sailed as first mate on United Fruit ships; I lit candles at church daily, praying for I knew not what. Story of my life. In my story, "Jolie-Gray," a teenaged babysitter protagonist targeted by her dried-up aunt's envy, including charges of trying, gakk, to seduce her dried-up uncle, retreats into intense prayer for deliverance. She's clueless as to what deliverance might look like. I'd been teased for drinking gin and tonic while reading the Bible (I'd never learned it growing up). I decided it'd be fun to have Jolie-Gray drink fig wine every afternoon while praying. Eventually, her tissues suffused with fig wine, she bursts into flame (human spontaneous combustion has an honorable literary history, not confined to the National Enquirer), her fingers held high candelabra-style, on the bow of a banana boat aiming out the mouth of the Mississippi toward Ecuador. There's no linear, logical solution, so the mind leaps sidewise into magic. I'd been visiting outside Beijing in 1989 during the student demonstrations that culminated in the June 4 massacre. I wrote a story, "The Angels of Tian-An-Men Square," that expressed the pain and glory of that time. In 1992, I returned to China to lecture and do research. En route to the airport, departure day—July afternoon, heat shimmering over the pavement—in my peripheral vision I saw something peculiar. Circus tent? Old-fashioned skating rink from my childhood? No, merely heat mirage. A story, "Pavilion," began forming: heat and disorientation plus pained recall of June 1989 toppled me into magical realism. I wanted transcendence this time, though as usual I could not direct its course. (A former colleague—with a DNA transplant from an engineer?—once constructed a tidy equation for generating magical realism. I think not. You have to suffer to be beautiful.) Sundry folks from all corners of China are mystically drawn toward Beijing—maybe in the fashion of the movie, Field Of Dreams. If Ray Kinsella, Kevin Costner's character, builds it (a stadium in the cornfields) they (Kinsella's dead father, plus deceased baseball teammates, then later serpenting miles-worth of cars, headlights all aglow) will come. In "Pavilion," (coming in Glimmer Train Stories, 2010) folks come bearing canvas and bricks, wood and wax, paint and provisions. They build a skating rink, oval as an egg and full of promise: an alternative version of the '89 massacre, ending gloriously. I'd grieved for years for Vietnam vets, thinking to write about a Vietnam amputee, but didn't know how to start. Too painful. I started anyway. Rapides Valcour, a gentle Cajun guy who's lost his legs to an exploded Claymore mine, marries a sweet diner waitress who sees nothing but his great bayou-brown eyes. The day after their wedding, he says to her, "Honey, you gone have to raise me. Ain't nobody raised me. I ain't regular." He means something way beyond war, farther back: childhood abuse. I prayed, Let this cup pass. You can't undo that stuff. Or can you? I kept writing. A burst of light imploded deep within me—as if a holistic practitioner were working above me, not even touching my body. Silent, epiphanic. I had my solution. But as those silly, smelly boys said in third grade book reports, "I won't tell you the ending. You'll have to read the book." Or in this case, a short story easily available.

| |